Locals call it “The Tomb,” but it is more generally known as the Runit Dome, named for its island home, Runit Island. Made of eighteen-inch thick concrete, the structure itself was built over a crater left from a nuclear test explosion to house the waste from cold-war era testing performed in the larger Enewetak Atoll region.

“Testing” can sound innocuous and neutral, but this is really the debris from the over 40 nuclear bombs that were detonated across this small chain of islands. In four such cases, the islands that were targeted were completely annihilated. And now, nearly 50 years later, the concrete that covers the “85,000 cubic meters” of nuclear waste is crumbling and the sea laps at its edges. And that’s just the top; the bottom was also meant to be lined with concrete but that action was deemed too costly and, given the nature of sand and dirt, the radioactive material is exposed to sea water from below.

While the United States has acknowledged that a strong enough storm could cause the dome to completely crumble, “a 2014 US Government report says a catastrophic failure of the structure would not necessarily lead to a change in the contamination levels in the waters surrounding it.” How comforting you find that will depend on how fully you trust public statements by the United States military.

For all of this, we don’t really know what the effects of the catastrophic collapse of a structure that was supposed to be “temporary” would be. The region has indigenous residents that “only” count in the hundreds. And seafood from the region is already banned for export by the U.S. government. Of the nearly thirty islands that remain in the region after the testing, there are only three that are considered habitable. With the dome intact, it is a region already as haunted as Chernobyl, but without the same level of name recognition; what would be the effects if the dome collapsed and the waste, which “includes plutonium-239, a fissile isotope used in nuclear warheads [...] and is one of the most toxic substances on earth,” sinks into the ocean? And if it did crumble and leak out, when would we know? If it's already leaking from beneath, as scientists and island residents conjecture, who would tell us?

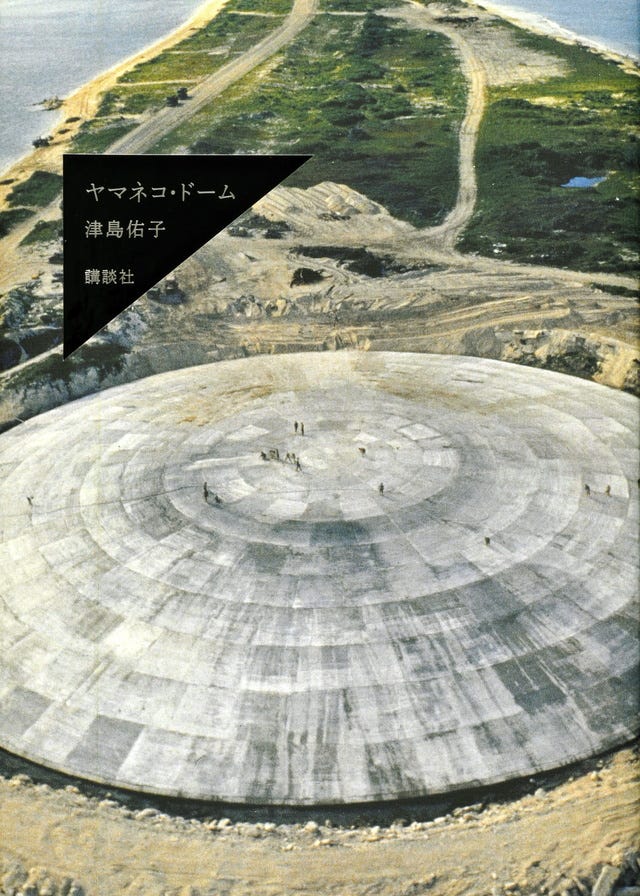

This is the “Dome” of the title of Tsushima Yuko’s 2013 novel ヤマネコ・ドーム (Yamaneko Domu) translated into English as Wildcat Dome by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda and to be published by FSG in March 2025. The original Japanese hardcover edition even has on the jacket an aerial photo of the concrete structure itself. But, in both the Japanese original and this English translation, the word dome/ドーム does not appear in the text until the author explains in a postscript about the concrete dome structure on Runit Island. And this is a novel that foregrounds the Fukushima nuclear plant disaster in both the jacket copy and the text itself, not the Runit Dome. So what’s going on here? Even the other word in the title, Wildcat /ヤマネコ, only appears a handful of times and then just the word, not the animal itself, as it were.

So no dome and only the rumor of wildcats. What is a reader to make of the title as they read?

+++++++

The experience of reading Tsushima Yuko’s late work, and specifically her novel Wildcat Dome is a singular one. I’ve read this particular novel several times in both Japanese and now in Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda’s new English translation, and as I read and re-read, I can sense the way the world not portrayed directly in the text presses in on the characters and their lives, as it does in our own lives. This is through her prose style, but also her use of onomatopoeia and folk songs. Those sounds, whether singing or from the natural world, create a feeling of closeness for the reader, of sitting directly next to the character, or of hovering at their shoulder, like an angel.

For example, in historical fiction, like Tsushima’s final completed novel, 2016’s ジャッカ・ドフ二:海の記憶の物語 [Jakka Duxuni: A Tale of the Memory of the Sea], the story vacillates between 2011 and the 18th century; in 2011 the character we’re following chants verses to herself, each line of which begins with: ノックルンカ / Nokkurunka. Starting from those little touches, the style and narrative construction through the rest of the book let you know these characters – a young Ainu girl named Chikkup and a slightly older priest-in-training named Julian – exist within the cultural and political pressures of 18th century Japan (maybe most famously portrayed to Americans through Endo Shusaku’s novel Silence [沈黙], adapted into a film several years ago by Martin Scorsese). But the narrative is not about raging against these systems and prejudices, or even coming directly into conflict with those forces as in Silence; it’s about the characters living their lives as best they can given the reality of these exigencies, even if they never encounter them in the narrative except in ambiguous and indirect ways.

This same technique is at work in Wildcat Dome. Shortly after the narrative starts, we’re treated to the buzzing of insects: ピシ ピシ ピシ ピシ / pish pish pish pish. And from there, with that sound of metallic insects crawling over tree branches and bark, devouring leaves, we enter Mitch, Kazu, and Yonko’s life. These three main characters around and between the consciousnesses of whom the narrative swirls, cannot help who they are and when they were born and what events they live through.

Mitch and Kazu are children of mixed parentage. Born to Japanese women, their fathers were American servicemen who left at the conclusion of World War 2 and of their role in the occupation that followed. Its not known for certain in the text, but more than once the implication is that they raped the women who would be Mitch and Kazu’s respective mothers. Or maybe not. Maybe it was prostitution, or a single night’s mutual passion. Again, the text gives no confirmation, just guesses, theories. Regardless, for one reason or another (we, again, never know for certain why) both are left in the care of an orphanage for these mixed children run by Mother Asami, a Catholic nun. In 20th century Japan being mixed race was to be the object of prejudice, suspicion, and bullying. For example, it was only in 2022 that there were news stories of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government finally repealing rules for secondary schools in Tokyo that students must have black hair. Not undyed hair, but black hair.

But that’s just the environment the characters are born into. That prejudice comes into play in an elliptical way in the narrative. After much agonizing, remembered by the secretly observing Mitch and Kazu, their adoptive mother decides to send both of them to boarding school in England so they can escape the prejudice they’ll experience in Japan. (You can make your own inferences about what it was like in Japan from that.) But that exile doesn’t stick and Kazu and Mitch are back in Japan with their adoptive mother, called Mama, after only two years. We never even read about their time in England, we just know that it was bad and that, given the choice between two cesspools of prejudice, they would rather be with their family so they decided to return. At no point do we witness prejudice playing out for them, it’s just understood. The point is not to feel sorry for them, or understand their plight in a gesture of coercive empathy. This is just their life and they have to live it; how you feel about it doesn’t really matter.

This is a quality that sets Wildcat Dome at a remove from recent popular fiction in America. This narrative is not triumphalist in its naming of racism and sexism – although the reader is never confused about why the orphans are discriminated against. It’s also not raising awareness of a problem, although that may be a byproduct. Mitch, Kazu, and the other orphans are not puppets for Tsushima to make a point. There are no victories, per se. No one wins. What would there even be to win?

++++

The narrative of Wildcat Dome weaves in and out of the separate voices and memories of the characters from the time immediately after Japan’s defeat in World War Two when they were children, through to the time just after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima Disaster, when Mitch, then in his late 60s, returns to Japan for the first time in the years after Kazu died to try to convince Yonko to evacuate.

Mitch and Kazu, as they live their lives that span most of the second half of the twentieth century, have an ambiguous relationship with Japan. They both are defined by it and reject it – even as they can never entirely break that relationship. To the outside world, they’re Japanese, even if inside Japan they are still outside, as it were. The events that define Japan to the rest of the world hang around their necks exactly as events of their childhood define them to other Japanese people. A conversation Mitch has with a Danish woman, Sonia, a lover who he may or may not have fathered a child, Niels, with, is illustrative of how the world sees Mitch (and how Mitch sees it in return):

“Tell me, what was it like? You’re Japanese, so you must know about radiation, right? I’ve seen the photographs of those poor people who suffered horrible burns. [...]

“I’ve never been to Hiroshima or Nagasaki in my life, Mitch responded angrily. I don’t know anything about it. Why would you ask me something like that? All the things you want to ask me about aren’t particular to me, they’re things you could ask any Japanese person.”

And yet, while the world beyond Japan sees him as imbued with a kind of racial memory about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan sees him as not Japanese. Or at least as tainted in some way, as in this (imagined) monologue by a dead friend, only for Mitch’s ear:

“But you know, Japan is a strange, terribly conceited country that hates outsiders, so you have to be careful. You’re likely to be bullied wherever you go because of how you look. Terrible things are lying in wait for you.”

That warning, delivered late in the novel, is key to their whole journey, Mitch’s, Kazu’s, and that of the other mixed race children from the same orphanage. When they were quite young, no more than 7 or 8 years of age, one of the other orphans, a girl named Miki, drowned in a pond, her orange skirt blossoming outwards on the water surface, creating a lifelong psychic wound. What happened to Miki? How did she drown? Was she pushed? Mitch and Kazu and Yonko, as well as maybe some of the other children, were all there. Or were they? Was it another neighborhood boy, Tabo?

Tsushima, through a technique that tells the story only through the minds of its protagonists, never allows us any certainty, as much about everyone’s origins are uncertain. The further away from the past we get, the less anyone knows for sure. Because of that uncertainty, the color orange haunts their lives. Whether in future deaths of women wearing orange that they read about in the newspaper, or in the carnage of napalm in the jungles of Vietnam, the very allusion to the color orange is enough for that psychic wound to throb. They are never allowed to ask forgiveness or to forgive themselves; they aren’t even sure that they did anything or that there was anything they could do. As with the circumstances of their own births, what forgiveness could there ever be?

++++

Tsushima Yuko’s late period fiction, like Wildcat Dome, has always been about dealing with tragedies that are personal, cultural, and political. In Laughing Wolf [笑うオオカミ], a seventeen year old boy leads a twelve year-old girl – the daughter of a woman who entered into a suicide pact with the girl’s father in a graveyard in winter, an act which the boy witnessed as a young child and had a role in the woman’s eventual survival – on a journey in postwar Japan, ostensibly towards Siberia. In あまりに野蛮な [Too Savage] a young woman in Taiwan in the 1930s deals with the tragedy of losing a child, in what was at the time one of Japan’s colonies, as the brutality of the Japanese Imperial regime begins to increase dramatically towards what we now think of as World War Two. Seventy or so years later, Lily, the granddaughter of the main woman, Mischa, retraces Mischa’s life as recorded in her letters. In ナラ・レポート [Nara Report] a young boy, whose mother’s death has, basically, deranged him, slaughters one of the herds of deer that hangs around the park by the temple of the Great Buddha in Nara, triggering a larger destructive journey, all while haunted by his own ghostly construct of a mother’s voice, mixing both his own mother’s voice and that of the mother of the deer. Even in her two collections of essays that came out between 1998 and 2016, called アニの夢・私のイノチ [My Brother’s Dream・My Life] and 夢の歌から [From Dreamsong] respectively, she grapples with the death of her close friend from cancer in 1992, even as she also grapples in the same text with the Fukushima disaster, wondering how her friend would react to that event and others that occurred since his passing almost twenty years earlier.

Though the search to connect events in an author’s biography with the creative work they produce can be little more than an exercise in cutting a work of art down to a size that the critic can then control, there is no question that Tsushima’s life was one marked by personal tragedy: her father – notorious writer Dazai Osamu – committed suicide with his mistress when Tsushima was just one year old; in 1985 her son died at the age of eight of a respiratory illness; and, as already alluded to, in 1992 her close friend, author Nakagami Kenji (criminally under-translated into English, imo) died from cancer at age 46.1 Having never married, she gave birth to two children, giving her the status of a single mother which brought with it its own marginalization in notably conservative Japanese society. “A conceited nation,” as quoted earlier. Each of these events and circumstances found outlet in her fiction, though they are no more than the germs of her creative expression.

All of these threads – of tragedies that are personal, political, cultural, and historical – come together at the end of Wildcat Dome, which I take to be one of her most accomplished late fictions. A 60-something year old Mitch returns to Tokyo after a long absence to see the damage of the earthquake and the explosions at the nuclear plant in Fukushima. But really he’s there to plead with Yonko to evacuate with him. To leave the blasted island for good. Upon arrival, the Tokyo air is a soup of silvery radiation to his eyes, though the people he sees continue their everyday lives as if all was normal. This return for Mitch is eternal. He’s always running away and returning, only to set out once again. It is the same for all of the orphans, most adopted out to American families in their youth. As the children of American GI’s, this is an irony they feel deeply. But still they go away, then they come back. Always anchored to Japan.

For years, Mitch had denounced Japan, wishing this hateful country would disappear from the face of the earth. [...] Mitch didn’t want to go back to Japan. He wanted to forget all about it. But now, learning of the tsunami and the nuclear accident, he realizes his hatred of Japan only reveals how much it means to him.

++++

The Runit Dome is not exactly a secret – structures that are that large and odd looking are difficult to hide – but it is trying to cover over something, a byproduct of war or the preparation for another war. And while I don’t want to stretch the metaphor too far and suggest a comparison of the mixed race orphans of war with nuclear waste, that doesn’t mean Japanese society hasn’t tacitly treated them similarly. Maybe the dome is covering the emotions and scars held by those forced into the margins by a whole culture.

In an 2013 essay entitled 私のヤマネコたち [“My Wildcats”], Tsushima gives more insight into the title of the novel. She starts by recounting a day in her garden, almost a week after the great earthquake in 2011, when she suddenly felt like she was being watched by a wildcat. Some primal fear overtook her for just a blink of time, and then she realized a neighbor’s cat was watching her from the garden wall. She felt silly, but that moment stuck with her, and as the societal reaction to those living in the zone around Fukushima began to curdle, she remembered that feeling of being watched by a wild animal.

This leads her to consider what she calls 「見えない存在」or “Invisible lives”, and how, scattered as these lives are, they’ve been here the whole time. Not just those orphans of American GI’s, but all of the dispossessed. She connects this insight about those lives to those she has unconsciously portrayed in her prior fictions, starting with 火の山:山猿記 [Fire Mountain: The Diary of a Wild Monkey] in 1998 all the way through her, at the time, most recent novel, 葦舟、飛んだ [The Reed Boat Flew] in 2011. And then she turns to Wildcat Dome and her “wildcats.” Reflecting on their fate, Tsushima wonders how much more open and generous Japanese society may have become if it had welcomed those GI Babies [GI ベイビー] as a member of the in-group from the beginning.

But that isn’t what happened, and those orphans, as she says about the people who live in nuclear areas, they too know that, as eternal outsiders: ”The deeper ‘inside’ they go, the more a silence spreads.”2

Fun Fact: Between when he found out he had terminal cancer and when he died, Nakagami is reported to have said “Please just let me live longer than Mishima,” referring to Mishima Yukio, noted author, right wing terrorist, and samurai cosplayer, who committed ritual suicide in 1970 at the age of 45. Nakagami got his wish and died at 46.

[...] 「内」にいれば入るほど、そこには沈黙が広がる[...].