Culture, Digested: What Was Woke Art: Elite Interiority

Curtis Sittenfeld's Rodham and other fan fictions

Part one of who knows.

The whole of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign was twisted around. “I’m With Her.” Shouldn’t it be the other way around? Isn’t a politician supposed to be with us?

And when she lost, a lot of women took it personally. This happens every campaign, of course. You pick a representative. Someone to speak for you and work with your values. When you pick a losing team, it can feel as if your vision for the world and how it should work has been rejected.

But there was something else going on with Hillary Clinton, who presented less of a vision for policy and more of a vision of a world where a woman could be president. We weren’t being asked to vote for her for what she would do — she had all the vague rhetoric that has become typical for Democrats, a better world, somehow, out there, moving forward, hope and change — but to prove that we also wanted to live in a world where a woman could be president.

Of course, then, she had a dedicated fan club of women who also wanted to tell their daughters they could be president one day. High achieving professional women, a lot of them in the media, who were not open to hearing criticism of their fave. All this was in line with the convergence of politics with entertainment culture.

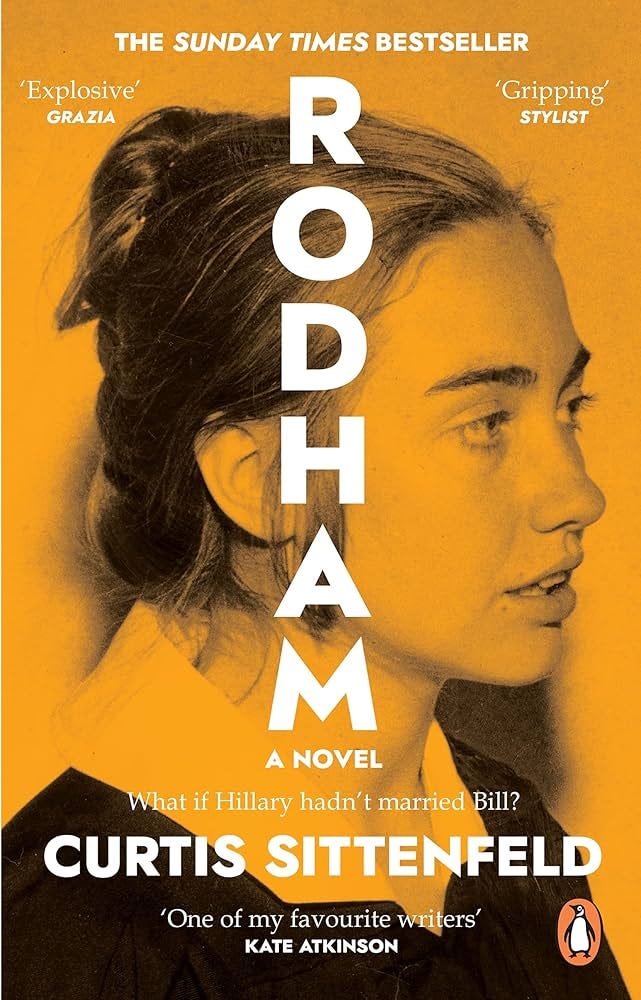

It’s not surprising, then, that Hillary Clinton got her own fan fiction, an alternate history version of her life by Curtis Sittenfeld called Rodham. It was perfect for Sittenfeld, whose protagonists were often much like the Hillary fanbase: grad students, creative professionals, ambitious women just slightly not happy in their work-life balance. Published in 2020, after her loss of the 2016 election, Sittenfeld wanted to imagine a world in which Hillary could have won. But instead of happening on a Livejournal, where such cringe material is supposed to live, it came out in hardback from a major publisher. It is a pitiful, almost achingly sincere document, which makes it an interesting case study for understanding one aspect of woke culture, which was asking the audience to invest themselves imaginatively, emotionally, and financially in the elites.

Fan culture is less about being entertained these days, it’s about identifying with someone. Pop culture figures act as avatars that are animated by their fans’ projections.

It became important for stars, then, to become as flat as possible. Any detail that is not relatable to the masses makes you a bad stand-in for an audience. If your public persona becomes compromised, your public life is put at risk. The most extreme version of this is seen in South Korea, where film, TV, and music stars become unemployable with even the smallest whiff of scandal or transgression. Drug possession, DUI, an extramarital affair and all of a sudden you’re a pariah, your career is over, and stars have a high suicide rate as a result.

In America, a lot of cancel culture was about weeding out figures who could act as aspirational stand-ins. While some of the behavior was criminal (::cough:: Kevin Space ::cough::), a lot of it was about having the wrong opinions about Israel, using the wrong language for gender and sexuality, or being associated with people already deemed inappropriate. There was no statute of limitations — things said or done in college were fair game. If you were considered irredeemable in mass liberal culture, then you could essentially serve the same role in antiwoke culture, which was also undergoing this transformation from entertainer to stand-in.

Much of this reinforced the central principle of liberal lifestyle: the human being is improvable. It is the responsibility of the human being, in a liberal society, to use the institutions available — university, psychotherapy, media — to improve oneself, to create a better person and therefore a better society. Therefore the aspirational figure didn’t have to be only accomplished and credentialed but also good, moral, “healthy.”

Who better to have a clean record of social acceptability, opinions that were “on the right side of history,” and no misogynists or racists in their family tree than the elites? They had been undergoing an intense purification process since birth, making sure every action, word, and deed made them more employable, better on paper, and more acceptable to admission committees. In millennial pop culture, the biggest celebrities and emptiest vessels like Sabrina Carpenter, Ariana Grande, and Taylor Swift have all been stars since childhood. And in the “higher” arts of literature and visual art, the most successful are those who have gone through extensive educational programming.

Maintaining relevance often means embodying a relatable archetype. In literature, there are the Sontag girls, the Didion girls, the Babitz girls. There is no divide between public and private life, so the creative has to constantly re-present herself to the audience through personal essays, autofiction, and social media approachability. There was a very small patch of land to stand on between relatability (I like Taylor Swift, just like you!) and aspirational (I have two boyfriends, I live in Europe, I have a better book deal), so readers could, and would want to, insert themselves into the works and their lives.

After all, your faves are not just faves, they are holding space for you within public life. Their success is your success. Which is why they must be defended, sometimes vociferously, from criticism or backlash, and why fans do the work of bumping the numbers of their streams, creating propaganda and works of inspo, and publicizing their material.

Also in 2020, employees at Hachette walked out to protest the forthcoming publication of a book by accused child abuser Woody Allen. This was quickly followed by a walkout to protest the publication of a book by accused TERF JK Rowling. The Allen book would be canceled and shuffled off to another publisher, which was quickly becoming known for specializing in “antiwoke” literature. The Rowling book, however, stayed with Hachette.

But the takeover of the lower levels of publishing by the Ivy League-educated that had started in the millennium was at that point almost entirely complete. There was a consensus of opinion forming about who was acceptable and who was unacceptable. The figures chosen as unacceptable were so because of particular views on different segments of the population. Woody Allen mistreated women/girls, JK Rowling spread hatred for trans people. Publishing someone “bad” was a form of platforming their bad ideas.

The hottest literary critic of the time was/is Andrea Long Chu, whose long essays on single subjects were sure to go viral because of the memorable zingers she crafted. (Hanya Yanagihara is “a sinister kind of caretaker, poisoning her characters in order to nurse them lovingly back to health.” Ottesa Moshfegh: “It must be convenient to believe in a God whose theological features consist in giving you divine permission to write whatever you want.”) But the reason for the popularity of Chu’s shtick has less to do with the insight she has into literature and more for her ability to take the symptom of a bad book and diagnose the writer with being a bad person. Zadie Smith is boring because she is a liberal (which is bad). Rachel Cusk’s novel is rigid because she is a gender essentialist.

In Sittenfeld’s Rodham, Hillary Clinton’s political failings are also personal. When Sittenfeld imagines a version of Hillary who can win the presidency, the change she makes is not ideological. It’s not her eagerness to reshape the world through military intervention, nor her willingness to sell out the working class to gain political power, nor her cronyism or nepotism. It’s her loyalty to her husband, Bill.

Bill’s problems are also personal. He mistreats women and is so charismatic that he faces few consequences. His misogyny is a festering wound that, had it been corrected, could have led him to be a better man and leader. Hillary’s loyalty to Bill and her refusal to leave him despite scandal and betrayal is the point Sittenfeld seems to think Hillary went wrong. Hillary’s problem is not that she is too ambitious, it’s that she’s too loyal, she loves too much, and maybe she doubts herself too much as well. Sittenfeld, correcting the timeline to create peace and erase the presence of big baddie Donald Trump, has her fictional paper doll version of Hillary leave her husband, which inevitably leads to her ultimate success.

In each case, the political and the personal are deeply intertwined. Having the wrong political viewpoint is a personal failing, a sign that there is something wrong with your character. Correcting for that political problem means correcting yourself personally. There is no separation between one or the other, you cannot be a good person and politically misguided. Nor can you be a bad person (a rapist, or someone who has used a slur in the past) while also being politically effective.

This also conveniently corrects the largest political problem of Hillary Clinton: she was not an aspirational figure. No one wanted her life. No one wanted to imagine themselves in her shoes. The political success, sure. But the marriage to the cheater, the stifling your anger and hurt for the sake of political success, nah. But a liberated Hillary, having reclaimed her maiden name and offering a vision of true independence and success, that is someone more people, at least in Sittenfeld’s imagination, could support.

Part of the problem with this segment of woke art is that not everyone sees the liberal elite as aspirational. In fact, it’s a small segment of the population who wants to be like that. It is possible to disagree reasonably with what the college educated have established as the norms of political and personal life. It’s also possible to be bored by the inner monologues of well credentialed veal calves that has passed for literature in the last ten years.

Believing that the liberal/leftist lifestyle (I know they pretend to be at war with one another, but other than having slightly different opinions on political matters they are of the same class, same schools, same mindsets, same lifestyles) is the peak of American existence requires a fundamental belief that the educational system is a meritocracy, that ideology reflects character, and that the people handpicked to be experts by the institutions of American society have your best interests at heart. None of these things are true, and it’s easy to demonstrate how wrong all these things are, and yet the American woke artist refuses to engage with the possibility of being wrong. The works that come out of this woke urge help to reinforce these delusions and create the idea that nothing else is possible.

Rodham got some terrible reviews, everyone immediately spotting its ickiness. But I’m not convinced there is much to separate this fantasy of a woman wisely wielding power without being tempted to abuse it or to crave it for its own ends rather than a wide-eyed desire to do good from Sally Rooney’s romances about creative professionals or Brandon Taylor’s romances about grad students etc etc. We as readers are being asked to invest ourselves in the inner worlds of our elites, whether they come in the form of the imaginary first female president or a guy who got into Columbia’s MFA program.

Recommended:

I reviewed Curtis Sittenfeld’s new collection of short stories for the Telegraph.

Like everyone else, I liked Sam Kriss’s take on the anti-woke alt-lit scene. We have no hope of ever getting a good book to read again, apparently.

A common thread on America’s problem with addiction: we have the solution, but we’d have to treat addicts as something other than moral failures to give it to them so we’re not going to do that. A drug is extremely effective in getting people off fentanyl, but it doesn’t punish the addict so it’s not getting used. Very similar to the drug that is effective in helping alcoholism, which is not getting used because we only understand alcoholics as having something wrong with them.

I reviewed Emmalea Russo’s Vivienne for The Metropolitan Review

I read that Sam Kriss essay you linked to, and I have to say there are times when I feel relieved to be completely out of touch with what is going on. I didn't know about any of the books he wrote about. I did know about the Rodham book, which means there is more I can do to insulate myself against the many threats to my well-being. I also understand even better now why no one wants to publish my novel about cannibals who never go online. I should have written about cannibals who go online.

I think the solution is for everyone to have to watch and read Demon Slayer. It's the only way to fix literature. If you want to publish a novel, you should have to first describe in detail what happens to Shinobu, the Insect Hashira.

I love Prep so much that I've been refusing to ever read Rodham in case it retroactively taints that book as well.

I agree with your definition of woke art, which is why anti-woke art is exactly its mirror image: "Pay attention to ME! MY (and my friends') personal matters and insecurities ought to be what matters most! MINE!"