Culture, Digested: The Worst Book I Read This Year

Jennifer Higgie's dive into the shallow end of mystical art and spirituality

When Hilma af Klint’s show Paintings for the Future opened in New York City, a lot of fuss was made about the coincidence of its venue. As Jennifer Higgie, former editor of Frieze, states in her latest book The Other Side: A Story of Women in Art and the Spirit World, the works were originally intended for “an unrealized spiral-shaped temple” meant to be built on Ven island in Sweden. Charmingly, af Klint’s sketches for this temple vaguely resemble the museum in which the blockbuster show ended up: the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Wright was commissioned for the Guggenheim the year before af Klint’s death, making the architectural rhyme one of those things, a slightly eerie synchronicity that biographers love because it tempts the reader to open a door to the possibility of fate. Like the notion that af Klint and Wassily Kandinsky were in different countries, involved in different social worlds, but at the very same time independently inventing abstraction. Like magic. Or the unseen hand of god. It enlivens the idea of the artist as a special figure, different in kind from the common man, without the writer just having to just come out and say that.

Higgie assumes af Klint would be pleased to find her work not in a temple for the spirit but in a temple of art. But in order to transfer the esoteric works from one venue to another, a larger process is required than simply making the works safe for transit and printing up some promotional materials. Designed as they were as an act of collaboration with an unseen spirit contacted through mediumship and séance, produced with the contributions of several women acting as a collective, and understandable through the religious and artistic symbolism that was relatively mainstream in artistic and intellectual circles at the time, their placement in the temple was intended for the purposes of enlightenment and worship.

But at the Guggenheim, the context changes from one of spirit to one of capital. Hundreds of thousands of visitors, paying a hefty entry fee and unlikely to be fluent in the theosophical and religious iconography of the late 19th and early 20th century, were asked to gaze upon the work in the way the contemporary audience has been taught to engage with abstract art: to pay attention to the feelings it evokes, referencing internal spaces rather than external or otherworldly realms. And then, at the end, consider buying some yoga pants screenprinted with af Klint’s works.

Of course this is what museum culture does: it, depending on your point of view, loots historical artifacts from a context in which they are useful and meaningful in order to turn them into commodities, or it protects and preserves the works while making them accessible to curious citizens of the world. Your own perspective on this might switch, depending on what you’re looking at, given the associations you might have to any given object. But in our secular age, the museum and the theater are often described with religious language, as if the artist was a priest or priestess and the audience their congregation.

This task of institutionalization and decontextualization is what Jennifer Higgie does throughout The Other Side, plucking artists and their objects from their beliefs, their ideas, their exoteric and esoteric communities, to turn them into artists rather than what they had previously been, maligned purveyors of woo. Her focus is on “mystical” artists, or artists who have some sort of connection to the occult, and that leads her to skip across centuries and belief systems, yet never straying too far from a Eurocentric core. Medieval Catholic composer and theologian and visual artist St. Hildegard of Bingen is given space next to Theosophist Surrealist Ithell Colquhoun next to 21st century self-described witches and pagans. She explains the idiosyncratic selection as being a result of her own particular interest and taste – this art critic and longtime editor of Frieze includes autobiographical interludes with anecdotes about a horse she had as a child and international trips she takes to look at art.

The work Higgie has to do to make these figures fit together is mostly the work of subtraction and oversimplification. Victorian painter Richard Dadd is one of the few men profiled, and to make his fairy paintings fit the brief of spiritual artists his psychotic break during which he murdered his father is reconsidered as a mystical epiphany. Higgie also writes about Annie Besant and her “thought form” collaborations as a notable moment on the development of abstraction timeline, leaving out any consideration of how these gouache works illustrating different moods and spiritual states might be informed by her activism as both a Theosophist and a socialist. Besant was one of the organizers of the “Matchgirls” strike of 1888, and her leadership of the Theosophical Society moved the spiritual organization into political realms.

Higgie’s engagement with these painters, from their truncated biographies to her focus on how the paintings make her feel rather than what the artists may have intended, serves to turn them into artists as we tend to think of them in the contemporary art market: singular geniuses working to express something about themselves through their chosen medium. This task reduces them, making both the artists and their work much smaller, simpler, easily digestible. The contemporary viewer no longer needs to work to meet them where they are, they can simply glide past them on the white wall of institutionalized art.

In doing this, Higgie not only recreates the market’s preferred forms of decontextualization, she also models the modern spirituality movement, which has been liberated from any religious structures or ideas about dogma. Higgie attempts to link these historical figures to contemporary artists working in a spiritual mode like Turner Prize nominee and instillation artist Goshka Macuga and the lighthearted fantasy works of painter Donna Huddleston, but the comparison only serves to make the contemporary work look especially wan and listless. Rather than the rich symbolism in earlier work, the imagery by contemporary artists refers to nothing in particular, nor is it sustained by the serious intellectual engagement with the world. Removed from the traditions and the theories of centuries of work, what we are left with is the spirituality of the shopping mall.

*

It is often said that this where we are now is a moment of spiritual revival. The mainstreaming of tools like astrology and tarot, the taking up of the symbol of the witch as an acceptable feminine archetype, workplaces hiring “spiritual consultants” to imbue their offices with meaning and ritual, the common use of language around “energy” and “the universe” all point in theory to an acceptance of certain spiritual principles and notions.

And tied into that, the work of women artists from that other spiritual boom – the turn of the 19th into the 20th century when Spiritualism was challenging mainstream Christian teachings about the workings of the universe and mystery cults were gaining influence throughout the Americas and Europe – have now become mainstream. Artists like af Klint and Georgiana Houghton have received more museum wall space, and political figures like Sojourner Truth and Victoria Woodhull whose associations with Spiritualist movements had previously been played down in their biographies are now being touted as pioneers in witchiness. It’s the women who get the most interest in this historical recovery, both because the political position of women throughout time is a primary topic of contemporary cultural discourse and because of our understanding of spiritual and occult movements as being antagonistic to the more monolithic, patriarchal Abrahamic religions. In this era of deconstruction and recentering attention on figures shut out of oppressive structures, the occult woman is a paragon of lost wisdom.

It's true that the history of civil rights campaigns and revolutionary movements of the era is tightly intertwined with the proliferation of magical societies, mystery cults, Theosophical and Swedenborgian organizations, and other occult communities. The popularity of spirituality during this time is given a diversity of explanations, from the scientific progress that caused widespread doubt to a Christian creationist explanation of the world to the overwhelming grief of families who lost members to any of the many wars fought between the American Civil War to World War I and so craved contact between this world and the next. These cults and societies tended to attract those looking to bypass the repressive dictates of the church, and its most fervent members were often the women, queers, colonized subjects who were being asked to sacrifice the most to conform to the theological standards for sexuality and behavior.

Whatever the reason for the widespread interest, there was an effort to take spiritual teachings out of the traditional hierarchies of religion that had proven themselves to be untrustworthy and circulate them in new and accessible ways. Gurus from India were introduced to American followers, who were eager to experiment with the yoga and meditation practices, without all the Hinduism stuff. Early feminist commentaries on and retellings of the Bible, like suffragette Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s 1895 book The Woman’s Bible, sought to separate out what was good about Christianity from what was mired in misogyny and hatred. It was fashionable to read and reference “exotic” texts like Buddhist literature and the Quran. It was a heady mixture of ideas, influences, practices, and outfits (orientalism was in peak form).

When scientific progress destabilized religious authority and the lack of meaning found in a pure rational worldview revealed science’s limitations, movements like Theosophy offered a kind of third way, a path toward understanding the world between science and religion. Theosophy was in conversation with both realms, using tools like magical practice to bridge the divide. Wisdom was something one pursued, through study, conversation, and ritual. And it was a remarkably intellectually fruitful time, producing lasting work like Varieties of Religious Experience by the Swedenborgian-adjacent William James and the less rigorous but still influential books by Madam Blavatsky and Rudolf Steiner.

There are easy parallels to be made that could bridge our time and this earlier age. The civil rights movements born then have fully come of age in today’s western societies. The secularization process started then has been nearly completed today. But the largest gap between then and now is intellectual. We don’t have spiritual communities; we have crystal shops. We don’t have prophets, we have TikTok astro girlies (“DM now to book a private reading!”) and Instagram witches. Basically, Spirituality dropped the part about seeking out universal truths and replaced it with a journey toward authenticity and self-discovery.

Jennifer Higgie is keen to list off an artist’s spiritual practice as if she were listing the products in their skincare regimen. Agnes Pelton was “interested in numerology, astrology, faith healing, and Theosophy.” Ithell Colquhoun “immersed herself in Druidry, goddess worship, freemasonry, tarot, Theosophy, and the Kabbalah.” Olga Frobe-Kapteyn was “immersed in spirituality, studying Indian philosophy, meditation, and Theosophy.” The repetition of the word “immersed” is interesting, as it suggests this is not something these women studied, that instead it was a liquid medium they splashed around in – maybe something like the therapeutic bath Higgie takes, describing it with more depth and in greater length than she goes into the religious beliefs of any of these artists -- the knowledge seeping into them through osmosis. And despite Theosophy’s repeated appearance in almost all the spiritual practices of the artists profiled, Higgie does not attempt to understand what Theosophy teaches, beyond her strange statement in its “belief in the universe as a single unit.”

She attempted to read Colquhoun’s book Sword of Wisdom, but she “struggled to understand its bewildering references to Christian mysticism, Paganism, Eastern religions, Egyptian myths, various alchemical practices, and magical traditions.” This collection of references does sound, though, like your average contemporary witch shop, with its smudging sage (Native American), Buddha figurines (Eastern religion), and crystals (assorted/fabricated), but removed from any philosophical or theological effort to weave these products and practices together. Higgie at one point attends a yoga class, and the instructor “plays a Tibetan singing bowl and tells us quietly that the world needs to soften.” She makes no effort to make the connection between yoga (a Hindu-related spiritual discipline) and a Tibetan singing bowl (a modern invention with roots neither in Tibet nor in shamanism as often claimed). It’s understood that what links them and makes them appropriate to bring together is their usefulness for “healing”. And that healing quality is accessible to all, even – or especially -- without all the religious baggage attached.

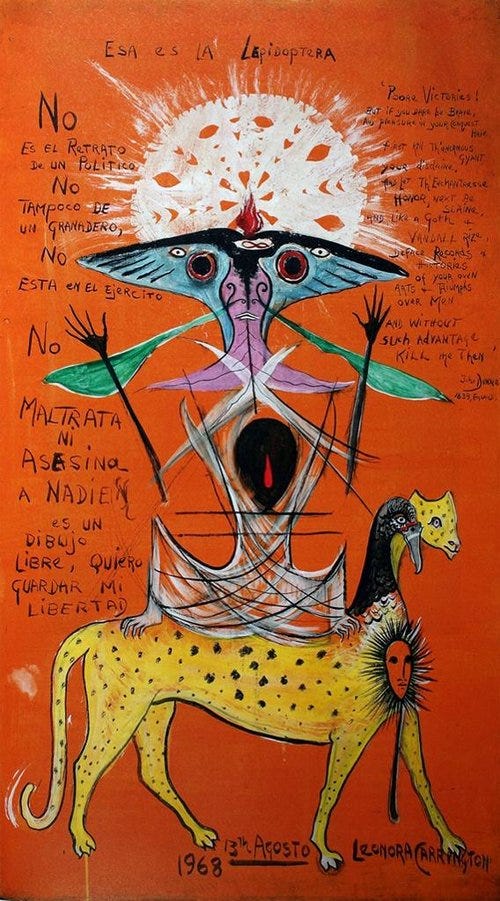

Easier, then, to strip the art of these larger contexts and references from the art, which conveniently also makes it easier to sell. In Higgie’s book, the liturgical compositions of St. Hildegard of Bingen become, drained of their meaning within her very clear cosmology, something akin to what you’d find on a meditation app. “I often played her music,” Higgie writes. “Its remote, celestial calm could make almost anything bearable.” Meanwhile, the auction prices of “mystical” artists like Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Colquhoun have been skyrocketing, and while part of that is due to the belated (and possibly temporary) interest institutions and collectors have been showing in women’s work, the turning of work often dense in religious symbolism and references into abstraction and “Surrealism” helps. And if a museum or gallery can sell a women artist-themed tarot deck in the gift shop as a tie-in, well, all the better.

*

Higgie frequently compares various women artists to witches. “But it’s not so long ago that a woman’s expressed interest in other realms might have ruined her reputation or even killed her – we all know the tales of women being branded as witches, cast out from society or burnt at the stake.” She quotes art critic Anya Ventura’s comments about af Klint as a kind of witch, one who “represents bodily and psychic independence – a figure in possession of secret knowledge gleaned outside the traditional structures of power.”

Everyone feels they are outside the traditional structure of power. Everyone feels like a misunderstood weirdo, a figure of such eccentricity that billionaire normie pop star Taylor Swift sings about how weird she is, how different, how misunderstood.

The witch has turned from being a figure of alienation and marginalization to one of aspiration. No longer does the witch manage the divide between the material and the divine, acting as an intermediary. She’s just another identity that requires only declaration and no real action, like feminist, like creative. The witch without knowledge is just a girl playing dress up, in the same way that ritual without the meaning to fill it just becomes empty gesture. Af Klint and the other artists written about here keep their knowledge occult – not because it’s still secret but because no one involved in this book is interested.

Recommendations:

I liked this essay on the sorry state of art criticism even before I noticed I was mentioned in it! It’s a nice antidote to that awful (and kind of embarrassing) Dean Kissick Harper’s essay.

Speaking of which, the media attention around the $6 million banana is embarrassing. The art world feels insecure most of the time. Art is both the Most Important Thing Humans Can Do and also a decadent world of useless humans propped up by money laundering and human suffering. So any time that something breaks through from the insular art space into the larger world of media, art people get excited. They get to explain something! They get to justify all this pointless information they have in their heads. Explaining why a banana taped to a wall cost $6 million is nonsense work, but a lot of people tried. And almost all of them used a series of increasingly cringe puns. Only two stories really cut through the noise, one was a profile of the produce seller who unknowingly sourced the banana and the other was a look into the criminal weirdo who bought it.

Per Faxneld’s Satanic Feminism was a balm after reading this Higgie book.

I really enjoyed this, as I always do your writing on spirituality and religion. I think about this a lot but I still haven't worked out how to effectively communicate my thinking in this area. I always find a lot of what I think expressed in your writing. I seem to end up ranting about the devil...

It is disturbing and, in my view actually evil, the way that contemporary "spirituality" has been reduced to the realm of feelings and imagination and vibes. It doesn't have nothing to do with that, but that's just the first step! You have to keep going, follow that thread until you are outside of yourself. Authenticity and self-discovery and healing are almost incidental.

People want God without the Devil. Want to feel the Good without having to deal at all with Evil. So these things that are supposed to be used to fight evil are instead sold as balms for anxiety. And that in turn keeps a lot of people from engaging with spiritual things on any level.

Any organized effort to engage with the ultimate good, the light of the universe, God, universal truth, etc, is going to get tainted by evil, that's how evil fights back. Eventually all most people can see is the evil so they can't engage with the original goal of the endeavor, the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment.

Many times over the years spiritual practitioners have intentionally stripped away most of the meaning, religious associations, the concrete systems of their beliefs, from spiritual objects or tools in an attempt to share some of the benefits with others and maybe that way entice them to embark on a genuine spiritual journey. And then evil got in, turned it into commerce and made the leap to something greater much more difficult.

So that's why I think everyone needs to go back to a REAL church with a LATIN mass... No, no, wouldn't it be wild if I took it there? I don't know what we're supposed to do but it does seem like the bare minimum we owe genuine spiritual leaders and communities like af Klint is to present their work in the context of their actual systems of belief and spiritual striving.

Did you read Julia Voss' Klint biography from a few years ago?

I love Klint's artwork and would really like to read something worthwhile about the milieu she was working in.