In Chime, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s 45-minute horror gem, the violence scares me. It’s certainly gruesome, but that’s not what makes it frightening. What’s frightening is the inability to make sense of it. The way it calmly yet suddenly arises. The combination of deadly focus and emotional vacancy with which it’s carried out, mirrored by Kurosawa’s perversely distanced, matter-of-fact presentation. The characters’ demeanor during the act of violence resembles serenity—something akin to a deep meditative state. It’s as if the commitment required of an act of violence—the necessary physical embodiment—provides succor in the face of everyday life’s irresolvable trouble.

This thought points to a moment in the film when someone asks Matsuoka (Mutsuo Yoshioka), a culinary instructor, whether people ever become overwhelmed with emotion while cooking. “Quite the reverse,” he responds. “People come here to calm their negative emotions. Looking at the ingredients, touching them, and savoring the taste calms people down.” He’s describing a common conception of mindfulness: engaging in the sensations of the present moment to ground oneself and stop clinging to and identifying with thoughts and emotions.

This detached manner of performing physical actions, free from judgment and identification, eerily resembles the way the characters in Chime perform, or attempt to perform, violence. They do so deliberately, dispassionately, and with undivided attention. Feel the rising and falling of the breath. Feel the knife in the hand. Feel the knife enter the body. This grimly echoes the U.S. military’s exploitation of mindfulness to create more efficient killers. That is, it’s the use of a spiritual practice sundered from any connection it once had to morality, ethics, truth—any sense of meaning—leaving behind only the vacant form. Chime takes this idea and the associated Buddhist concepts of no-self and emptiness and mines their horror potential. In a world without meaning, one that’s spiritually sick, these concepts become literalized and instrumentalized. They transmogrify into a means to become an optimized, perfectly efficient capitalist subject: an empty human form, a non-self, free of troubling thoughts, existing as merely the sum of its physical actions. Under these conditions, all actions, including killing, have no moral valence whatsoever.

Chime opens on a dismal, gray cityscape. The film cuts to an image of rumbling air ducts and tilts down to gradually reveal a teaching kitchen. Waves of light emitted from passing trains rush across the space as the camera creeps forward. Matsuoka circulates through the kitchen. He notices one of his students, Tashiro (Seiichi Kohinata), working alone and aggressively over-salting his food. This opening establishes a tone of eeriness and immediately suggests that something’s amiss. Eeriness transforms into dread the more we observe Tashiro. He isolates himself from the rest of the class, vacillating between states of obliviousness, catatonia, and intense agitation. Certain behaviors—such as scoring bread dough with rough stabbing motions or erupting in anger at mild redirection—hint at potential violence. He asserts that he has no desire to learn to cook; he’s seeking distraction from a torturous sound that no one else seems to hear: a chime “like a scream. But not human.” He says that half his brain has been replaced by a machine through which the chime controls him. Tashiro attempts to prove this claim with a horrific act of violence that results in his death.

Matsuoka, too, becomes attuned to the chime’s frequency. Soon after Tashiro first mentions the phantom noise, Matsuoka hears a chime-like sound with no apparent physical source, and his behavior takes a discomfiting turn. He acts strangely nonchalant after the initial shock of Tashiro’s death, yawning and stretching in a gesture of contentment before discussing the incident with a detective. “I think it went well today,” he says to his wife (Tomoko Tabata) later that same day, referring to a job interview he had. No mention of the brutal death he witnessed. At times, he evinces an eerie blankness redolent of Tashiro. At others, he’s manic, animated, rambling incoherently. He sees and hears things that others do not. He occasionally breaks into a sprint, for no discernible reason, with the urgency of fleeing for his life. He’s forgetful. Made aware at one point of contradictions in his comments, Matsuoka looks confused and vacant: “I’m not really sure why I said that. I don’t know what possessed me.”

The notion of being “possessed” gestures toward a radical self-alienation within Matsuoka. This condition bedevils characters all across Kurosawa’s filmography, perhaps most memorably in Cure. In that film, a nefarious drifter named Mamiya initiates hypnosis by repeatedly asking his marks, “Who are you?” They have no answer beyond generic, socially defined roles like “husband” or “teacher.” Underneath those layers of prefabricated identity lies a screaming void they refuse to face.

Matsuoka's self-alienation reveals itself most prominently in a series of job interviews for a head chef position. In many ways, Matsuoka’s behavior resembles the strange, depersonalized performance you’re forced to assume in any job interview. You’re not there to be you. You’re there to project what you think an employer wants. And what an employer wants is the most efficient tool to generate profit, not a human being and all the messiness that entails. Returning to the idea of mindfulness, these situations require presence, focus, and an engagement with the minute details of physical behavior, combined with an air of equanimity and confidence. They also require an eradication of the self and a sense of non-attachment to the character you’re projecting. Otherwise you might crumble under the weight of self-contempt and shame.

Matsuoka pushes his interview performance just into the realm of the grotesque. It’s deeply off-putting to see its depersonalized quality nakedly displayed. A cultivated air of confidence wafts off him as he eagerly volunteers to shed any aspect of his personality for the job. He talks about “giving the customers what they want” and not being “stubbornly attached to [his] tastes.” He punctuates these lines with a smile and finger-point that stink of phoniness—surely a gesture he’s mechanically rehearsed countless times. After this moment, the film cuts to a shot of the interview from outside, through a window—an image that doubles as a momentary retreat from the discomfiting display and a signal that what we’re seeing is all constructed surface.

Something odd happens at the end of that first interview. After Matsuoka says emphatically that he’d give up teaching if hired, the interviewer reminds him that he’d previously expressed pride in his teaching. Matsuoka seems shaken and addled by this. It’s as if he realizes that he accidentally let an inkling of his humanity slip through in a previous interview—a gross violation of decorum. But there’s also the sense that Matsuoka genuinely feels as if someone other than himself made the comment. This is the aforementioned moment when he says, “I don’t know what possessed me.” The interview process is fracturing Matsuoka’s identity.

We get a clearer picture of how and why in the last interview. Initially, Matsuoka completely breaks with his crafted interview persona. A manic energy animates his physicality, and an effusion of words tumble out of his mouth. He prattles on about himself. He seems desperate though insists he isn’t. The owner stops him, demanding that Matsuoka stop talking about himself. Matsuoka goes blank momentarily, takes a sip from his mug, and then attempts to switch back into his interview character. But here’s the problem: when he talks about himself, the owner chastises him for being too personal; when he expresses pablum about continuing the restaurant’s current direction (“Making the most of ingredients to serve authentic, everyday French cuisine at fair prices,” he says, in what must be the restaurant’s slogan) the owner wants to know what of himself he would bring to it. How would employing Matsuoka benefit the restaurant? The owner even appeals to Matsuoka’s artistry, directing him to ignore the profit-motive (as if they’d ever let someone in their employ do so in practice) and express his vision. How the fuck could anyone satisfactorily meet these contradictory expectations? Don’t talk about yourself but also explain what you as an individual can offer. Explain how you will be an anonymous tool that completely serves the employer and the bottom line while also asserting your unique artistic vision. It’s an incoherent position, and anyone would go insane trying to actually fulfill it. Ultimately flummoxed, Matsuoka concludes that, “It’s difficult to explain my qualities in words.” It’s difficult because he doesn’t know who he is or what he wants. Worse, he doesn’t even know that he doesn’t know. His thoughts and desires are not his own.

This unwillingness or inability to recognize what is just below the surface extends to the domestic front. Palpable, unspoken tension permeates Matsuoka’s home, which he shares with his wife and teenage son (Kiki Ishige). The three members of the household barely speak to each other and make no physical contact. When they do speak, the interactions are stilted and cold, often related to wealth or status. Matsuoka talks about his professional prospects. His son pitches him a cockamamie investment scheme and then assumes Matsuoka’s broke when it’s rejected. All the repression seems to be having deranging effects on Matsuoka’s wife, who, in one of Chime’s most unnerving details, compulsively recycles a seemingly endless supply of cans. Aside from the implication that she’s tidying up as a form of displacement, this is another instance of a character voiding interiority through immersive physical action. And it’s merely a noticeable distortion of her performance of other domestic duties, such as taking Matsuoka’s bag for him, putting away folded laundry, and having dinner on the table at the proper time. These routines, though not all disturbing on the surface, serve the same basic function.

We first see the bizarre recycling habit during a scene at the dinner table. During some idle mealtime chatter, Matsuoka advises his son that, while it’s good to have passions, “Don’t overdo it.” The son breaks into an involuntary fit of laughter. Suddenly, a rift in the protective facade has opened. Seeming to unconsciously recognize that repressed material is threatening to surface, the wife quickly gets up and recycles several bags of empty cans, making a racket in the process. The action initiates a reset. Everyone stops talking. No one acknowledges any of what just transpired. Unease and the clattering of cans fill the vacuum. The urgency of the wife’s behavior suggests fear, though she probably wouldn’t identify it as such. And if it is fear, what exactly is her fear’s object? Is it merely the potential for a moment of discomfort? Or is it something more ominous, like the threat of violence? Either way, we can infer that Matsuoka’s relationship to his career has poisoned the atmosphere in the home, and that little fit of laughter is the closest anyone’s getting to acknowledging it.

If it is, in fact, fear of violence that Matsuoka’s wife feels toward him, then it’s well founded. Matsuoka does turn violent, stabbing one of his students to death in a chillingly impassive manner. It’s here that the notion of mindful killing presents itself most noticeably. During the entire agonizingly long murder, which appears to arise out of nowhere, Matsuoka seems, quite literally, possessed. Any signs of humanity have drained away. (Compare him to his victim, who, moments before, was behaving like a decidedly non-optimized student and chef, complaining and being emotional.) His demeanor recalls Tashiro's claim that, while half his brain is controlled by the chime, the other half is still the same; so he maintains a rational mind. This suggests a state of surrender to whatever behaviors the body performs, with full awareness but no responsibility. Whatever happens is going to happen. You have no control. So why fight it? Why think about it? Just let it happen. Focus on the physical sensations without judgment. Become empty.

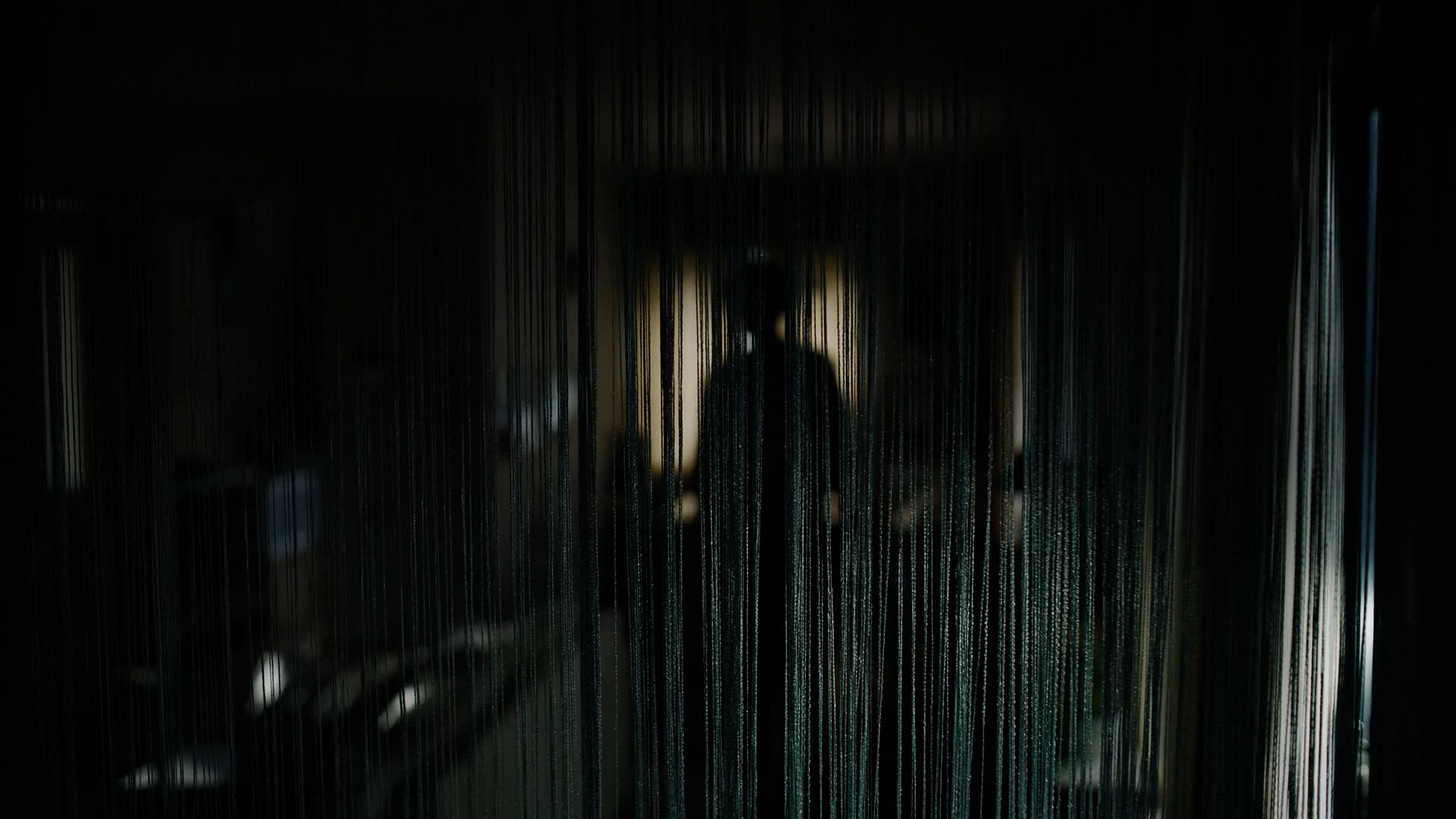

This hollowed out existence seems the end state that the characters of Chime are striving to attain. When Tashiro explains that wanting a distraction is the sole reason he’s taking the cooking class, he’s simply voicing a desire that organizes many of the characters’ lives. So perhaps hearing the chime is not a condition transmitted from one sufferer to the next, as initially seems likely. Perhaps the chime is something that’s already always there, and Matsuoka’s interactions with Tashiro simply made continuing to ignore its presence impossible. The chime, then, is best understood as something disavowed. Something too unruly, too threatening, too wrong to acknowledge and face. This idea animates one of the film's most striking sequences. Attempting to exit the cooking school, Matsuoka enters a dim, dreary vestibule. The space is a Kurosawa specialty: human-built yet hostile to humanity. It emits a belligerent array of high-pitched buzz, loose rattle, and droning airflow that can make your teeth hurt. Matsuoka’s attention alights on something offscreen. A mirror. He warily approaches, coming nearly forehead-to-forehead with his reflection, staring at it. While Matsuoka’s reflection in mirrors appears repeatedly in the film, this is the first and only time he’s shown looking at himself. The figure he sees is shadowy—indistinct. It—he—resembles a human-shaped void. He sees a stranger, and not one he cares to know. The malign ambient noise increases in volume to an almost unbearable degree. And then it stops. A jarring silence. Matsuoka stares for a few beats longer, turns, and walks away. In the reflection of the mirror, we see him move into the blurred background and out the door.

I can't stop thinking about the scene where the detective stops Matsuoka outside the school and, as they're leaving, offhandedly asks how we cut his hand and Matsuoka replies, "chopping vegetables" while making the stabbing motion.

Thanks for this post!

I haven’t been able to see Chime yet, but I watched Cure again recently to try to get a handle on it. Since Franz Mesmer’s work plays a central role in the film, I read about his method of curing ailments by potentiating a force that he believed all humans contain. I think that Kurosawa’s take on the “Cure” is that when we reach the zero point of capitalism, we embrace the hollowness of the self improvement philosophies that we are taught to define ourselves by. Mamiya is after all, just the missionary to “propagate the ceremony.”

I’m not sure if you like Thomas Ligotti, but there is a lot of overlap in his thematic concerns with Kurosawa’s. Two of my favorite of his stories are “Dream of a Manikin” and “The Town Manager”. “Manikin” involves the dissolution of the self, as a psychiatrist uncovers uncomfortable evidence that what he views as his personality is only a contrivance. “The Town Manager” is about the degradation of a town by predatory capitalism. Ligotti is also a lifelong resident of Detroit, and shares Kurosawa’s fascination with spaces that are “human-built yet hostile to humanity.”